Mixed Media

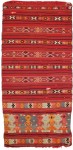

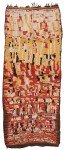

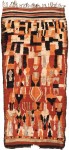

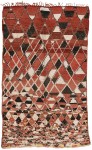

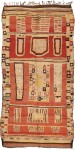

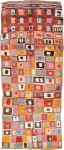

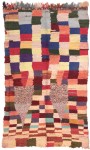

Moroccan rugs will never cease to amaze me. After over twenty-five years of hunting and gathering the Maghreb, from the Atlantic coast to the Atlas mountains and the arid Saharan desert, I am still mesmerised by the sheer ingenuity and versatility of Berber textile art. In particular, the last two decades of the previous millennium have witnessed the arrival on the Moroccan scene of previously unknown woven species. Collecting this material, albeit of relatively recent vintage, has allowed for the recording of possibly the last wave of authentic rural weavings arising from a still-genuine indigenous tradition. The photograph taken at ‘circa 2000’ will likely prove to be a very significant one, in that it will document the cut-off point between collectable rugs indicative of the material culture of the Berber people and those which have been woven to satisfy the demands of a growing market.

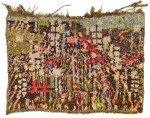

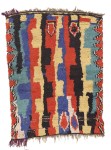

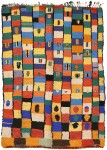

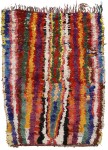

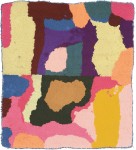

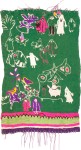

The trend-driven enthusiasm for Moroccan carpets has, however, been the catalyst for the present influx of a singular genre of weavings which had not been previously considered worthy of commercial interest – rugs which had been woven by Berber women for domestic purposes. These are often constructed by employing a range of materials, using the precious wool sparingly, and only when necessary towards the completion of what appear as very personal aesthetic projects. As an alternative to wool, these women utilise a plethora of materials, from rags to riches, often as a textural ingredient but also as a source of improbable colour. The combination of these fibres, which were the only ones available, reveals a pronounced artistic sensibility in expressing an intimate language, one that would have been significant only for herself or within the confines of a family or a tribe. Yet it’s truly endearing to be allowed within, to share in the arcane, personal vision and to feel the purity of its manifestation as a work of woven art. Aside from displaying the most ingenious fibre combinations known to the weaving practice, these also function as carriers of a vestigial language, expressed through abstract forms intimately connected to the Neolithic rock carvings present in some areas of the Maghreb.

I have chosen to present a selection of my most significant acquisitions of these weavings, including a cluster of earlier rugs as an indication of the continuity of its discourse. While the older examples occasionally offer a more mature attitude, as dictated by the need for economic use of the wool supply, along with larger formats destined for more high-visibility displays, the works of the younger generation of Moroccan women have been equally vital in continuing the tradition by venturing into more textural grounds, evolving the language from its earlier substrate into symbols of their time.

Catalogue Reference Key and Bibliography

Blazek 2005 – G. Blazek, Earth and Moon – Kilims from the Ourika Valley, HALI 139, March-April 2005, pp. 62-67.

Blazek 2013 – G. Blazek, High times in the High Atlas, Carpet Collector 4, 2013, pp. 38-53.

Hufganel, Adam 2013 – F. Hufnagel, J. Adam, Moroccan Carpets and Modern Art, Münich: Arnoldsche, 2013.

Korolnik 1998 – M. Korolnik, Fire and Water – Rehamna Carpets – Recent Field Research in the Plains of Marrakesh, HALI 99, July 1998, pp. 64-69.

Rainer 2005 – K. Rainer, Morocco Mon Amour, Graz: Eigenverlag, 2005.

Ricard 1926 – P. Ricard, Corpus des Tapis Marocains – Tome II -Tapis du Moyen Atlas, Paris: Paul Geuthner, 1926.

Saulniers 2000 – A. Saulniers, Splendid Isolation – Tribal Weavings of the Ait Bou Ichaouen Nomads, HALI 110, May-June 2000, pp. 106-113.

Vandenbroek 2000 – P. Vandenbroek, Azetta – L’art des femmes berbères, Bruxelles: Flammarion, 2000.

Viola, Sachs 2019 – L. Viola, A. Sachs, An infinity of stripes, HALI 200, Summer 2019, pp. 124-129.