Woven Art

Introduction

The early 20th Century witnessed a series of significant changes within the domain of art and design. The seeds of these changes had already been planted well into the 19th Century through the writings of A.W.N. Pugin and John Ruskin who, by idealising the pure, artisanal qualities of the pre-industrial medieval world, which made no real distinction between designer and craftsman, greatly influenced the thought of modern world pioneers such as William Morris. The revolution in design was soon imprinted by Owen Jones who, in his The Grammar of Ornament, compiled a plethora of reformed patterns which placed emphasis on flatness and two-dimensionality. This sourcebook proved to be fundamental towards the development of a modern iconography, especially as it pertained to the language of rugs.

The various trajectories in which these design reforms took place led to the birth of the first artistic movements across Europe. In 1902, the Belgian Architect Henri Van De Velde was named the artistic director of the Weimar School (which later became the Bauhaus), designing its flagship building in the Art Nouveau style. In 1907, he co-founded the Deutsche Werkbund, a German craft union which brought together a dozen manufacturers with an equal number of designers, and from which resulted a whole community of highly influential artists such as Josef Hoffmann, who designed the Palais Stoclet in Brussels and was one of the founders of the Wiener Werkstatte.

This early movement engendered a ripple effect throughout Europe. Even the storied traditions of France would eventually comply to these new directions in design, as we read in the catalogue of the 1910 Salon D’Automne, in which the art critic M.P. Verneuil suggests learning something from the German guests of the exhibition, although ultimately maintaining one’s Esprit Français. Already at the first Salon des Artistes-Décorateurs Modernes, held in 1907 at the Pavillon de Marsan, the controversial works exhibited by the young designers were in part a reaction to the commercial character of what had been shown at the 1900 Exposition Universelle, which consisted mainly of objects essentially reproducing French Louis XV and Louis XVI styles.

The first ones to follow the lesson were Paul Poiret and Louis Süe, who had visited Vienna together and were greatly in awe of the work of the Wiener Werkstatte. In 1911, Paul Poiret created the Ecole Martine, which was a workshop composed of young women of no formal artistic training who were encouraged to design and weave floral rugs distinguished by a child-like spontaneity. The success of this project prompted the establishment of many other ateliers, such as Primavera in 1912, directed by René Guilleré, the products of which were marketed through the large department store Le Printemps. The trend continued unabated by World War I, with the opening of La Maitrise in 1921, managed by Maurice Dufrène (which sold through Galerie Lafayette), then Atélier Pomone in 1922, supervised by Paul Follot (whose outlet was the famed Au Bon Marchè) followed, in the same year, by Studium-Louvre, directed by Etienne Kohlmann and distributed through Les Grands Magasins Du Louvre. In 1912, Louis Süe founded the Atelier Français, whose aim was to derive a new style from a revisitation of classical French design. Le Nouveau Style, an essay written by André Vera in 1912 for L’Art Decoratif, became the manifesto of the group. For the 1911 Salon D’Automne, Louis Sue presented a colourful carpet composed of a curvilinear garland of flowers overlaying a geometric, ‘Secessionist-style’ framework. This treatment of pattern was to become extremely inspirational for the artists most frequently associated with the Art Deco period (such as Paul Follot and Edouard Bénédictus), who were also known as Les Coloristes for the daring colour juxtapositions of their rugs and textiles. Louis Süe would then ally with André Mare, founding the Compagnie Des Arts Français (known also as Süe et Mare). For over a decade, they designed and produced furnishings inspired by stylisations of forms taken from the Louis Philippe period, yet adding Fauvist and Cubist overtones.

By the 1920’s, quite a number of artistes-décorateurs were involved in the manufacture of high-quality furnishings commissioned for the luxurious interiors of the Parisian upper class or for the capacious rooms of the French ocean liners—the opulent paquebots connecting Europe to America. Among these we cite important figures such as Pierre Chareau (represented here with a carpet he had commissioned to another artist, Jean Burkhalter), René Joubert and Philippe Petit (founders of D.I.M. – Decoration Interieure Moderne, a leading Parisian interior design firm, of which a major work is included here), and Ivan Da Silva Bruhns. The latter is widely considered to be the leading figure in carpet design throughout the Art Deco years and his signature Cubist-inspired patterns are synonymous with the period, to which we attribute here one unsigned example. By the time of the Exposition Internationale des Arts Décoratifs et Industriels Modernes, originally planned to inaugurate in 1916 but postponed because of the war and finally held in Paris in 1925, carpets were a firm presence in every respectable interior space.

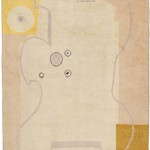

While the U.S. didn’t participate in the exhibition, they were quick to embrace some of the new ideas coming from Europe, incorporating them in the fast-growing architecture of its major cities. Both the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Museum of Modern Art in New York soon began to host a number of exhibitions dedicated to the modern decorative arts, stirring a considerable interest among the local artistic milieu. One of the leading innovative figures in the textile arts was Ralph Pearson, who took the traditional American hooked rug to a whole new level by employing local artists deeply steeped in Modernism. We are pleased to include here a superb example of this type, which condenses all of the explosive creativity of that period.

The burgeoning possibilities offered by the textile medium attracted great interest from the art world. Marie Cuttoli, then wife of a French senator and owner of the Maison Myrbor, gradually transitioned from fashion design to producing rugs in Algeria that were designed by leading Parisian avant garde artists of the period, namely Pablo Picasso, Jean Lurçat, Louis Marcoussis, Fernand Léger and Joan Mirò. These hand-knotted carpets, woven with the same technique as traditional north African rugs and conceived both for the floor and wall, had now officially entered the world of art in their own right as the subject of seminal exhibitions in Cuttoli’s Galerie Myrbor in Paris. Subsequently, the manufacture of these weavings was moved to Aubusson in France, which had an established weaving tradition since the 18th century and was the mill of choice for most of the floral carpets designed by the artistes-décorateurs of the period. We are particularly honoured to be able to present here two exquisite examples from Myrbor: a small Cubist-design rug by Marcoussis woven in Sétif during the early Algerian years, and a massive carpet commissioned to Lurçat and knotted in France for Helena Rubinstein’s palatial New York residence. Modern artists were continuously involved with the woven medium throughout the remaining part of the century, especially as there had been a growing awareness of how rugs could be especially helpful in representing minimalistic compositions made of blocks of pure colour. Included here is a mid-century knotted tapestry by Jacques Borker, woven in France, and beautifully exemplifying the Modernist development of design modules originating from Cubism, as well as a monumental work by Frank Stella, commissioned in India on the occasion of a landmark exhibition held in New York in 1970.

At the 1925 Exposition, one could already sense the beginning of the more austere, rigorous forms that would characterise Modernism throughout the 30’s and beyond. Le Corbusier soon began encouraging designers to embrace a more minimalistic approach to craft, heralding the shift from brightly-coloured floral patterns to abstract designs in muted tones, with an emphasis on texture and technique rather than composition and polychromy. An aesthetic revolution was soon to take place—the Bauhaus being a principal influence. The weaving workshops of the Bauhaus were essentially managed by two leading women, Gertrud Arndt and Gunta Stölzl, and their pioneering work was to mould the entire domain of the textile arts. Northern Europe had steadfastly followed the lessons of the Bauhaus since its inception, and one can appreciate this in the ingenious work of Scandinavian women such as Marta Maas-Fjetterström and Laila Karttunen, the latter being included in this exhibition with one of her iconic works.

Following World War II, hand-weaving became too costly and inefficient in supplying the heightened demand for floor coverings from a burgeoning real estate market. Through the detailed exploration of structure, one could devise the necessary conditions for creating prototypes for mass production. One of the main endeavours of both Le Corbusier and the Bauhaus was the mechanisation of weaving, and while this has indeed been one of the results yielded by Modernism, the world would eventually come full circle. We are now witnessing a social and aesthetic distanciation from the industrial, with calls to embrace the recyclable, the sustainable and the artisanal. There is a current renaissance of hand-weaving at work among contemporary textile artists, and one can only hope that exhibitions such as this one will lead the way in providing inspiration for many generations to come.